South America is famous for romance and religion; two concepts that seem to overlap regularly throughout history. Given the tropical climate that engulfs Central America and most of South America, and the common built environments (housing structures, etc.) in rural areas, South and Central America are also endemic for a number of neglected tropical diseases. For example: despite the fact that a yellow fever vaccine exists, there is a huge yellow fever outbreak happening in Brazil right now. This just shows that with the right environment, if preventative measures (like vaccines) aren't required, then the disease will prevail.

Aside from our well-known and beloved mosquito vector, Central and South America are also home to an incalculable abundance of other insects that have the ability to spread many different diseases. One of my favorites (so to speak), is the triatomine bug, AKA the "kissing bug" or the "assassin bug".

|

| Triatomine bug on a knuckle. Image borrowed from The Tico Times |

|

| Trypanosome cruzi next to a red blood cell. Image (c) to Pearson Education. |

Triatomine bugs, known for the unforgettable kiss I mentioned earlier, are nocturnal and attracted to carbon dioxide, which we emit constantly as we exhale. Humans exhale the highest concentration of carbon dioxide in one location while they are sleeping, because most people don't move around as much while they are out cold.

After biting an infected animal or human, the bug now contains the parasite and is able to transmit it to another being. The infected bug bites and draws blood for a blood meal while defecating on the surface of the skin. The bite is usually painless and doesn't wake the latest victim.

By including the act of defecating during feeding, the triatomine bug deposits T. cruzi onto the skin. A combination of the irritation of the bite, and a mild allergic response to the feces, causes the skin to feel itchy. Scratching the itch helps move the feces and parasites into the bite wound, and infection ensues. After scratching, the parasite can also make their way into the body via mucosal tissues in the eyes, nose, and mouth, reaching the bloodstream through penetration of the delicate tissues. The parasite needs the triatomine bug to break the skin, since it is too thick for the parasite to penetrate on its own.

| |

| This amazing image is from this publication. |

|

| This complete life cycle diagram is courtesy of the CDC. |

Fever and swelling of the lymph nodes kick off the presentation of symptoms. A sore may develop at the site of the infection, and if the person was bitten on the face, a presentation called Romaña's sign causes distinct swelling around the eye. Romaña's sign occurs in approximately 50% of infected individuals, and is often considered one of the tell-tale signs of infection.

|

| Romaña's sign in the left eye, image from the WHO and the CDC |

If not treated during the acute phase of infection, after initial symptoms subside, the chronic phase of Chagas disease sets in. Chronic Chagas disease can cause major complications to organs and entire organ systems, such as irreversible damage to the heart, intestines, and liver. Its estimated that over 25% of infected individuals develop potentially fatal damage to the heart.

Treatment for Chagas disease is usually a combination of benznidazole and nifurtimox, anti-parasitic medications that attack T. cruzi. This treatment must be given during the acute phase, when the parasite can be found in the circulatory system. In endemic regions, treatment is typically available. Yet, in the US, you must have a confirmed diagnosis of Chagas disease in order to obtain the treatment from the CDC, because it is otherwise not available. Diagnosis is performed by a blood smear viewed with a microscope to identify the parasite in the blood. Other tests, such as PCR, can be performed, but the blood smear is the gold standard in identification and diagnosis.

|

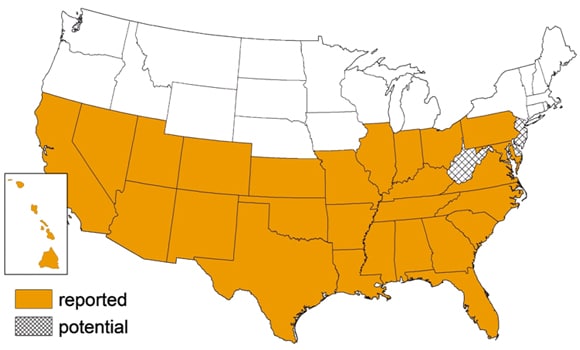

| Triatomine bug populations reported in the US, via the CDC |

The vector, triatomine bugs, are found throughout a large part of the southern US. A small number of locally-acquired cases have been reported, but not enough to cause huge alarm. Also, there are a number of ways this parasite can fail to infect you.Without the presence of the vector, the parasite cannot infect you. The parasite cannot penetrate the skin on its own, so unless a triatomine bug successfully bites you, or you have an open wound that is exposed to the feces of triatomine bugs, you are not at risk. Additionally, triatomine bugs don't always defecate when they feed.

The best way to limit exposure to Chagas disease is by reducing your exposure to the triatomine bugs, since there is no available vaccine, and treatment can be difficult to obtain in the US. Monitoring your house for triatomine bugs, cleaning away debris to reduce environments for their ideal hiding places, and if you are truly worried, regular insecticide spraying can all reduce your risk of exposure. While most insecticides have not been approved for use in the US against triatomine bugs, long lasting insecticides have been shown to kill them.

|

| Image from Chagas Initiative Argentina |