So, let's talk about this sudden burst of leprosy in the South.

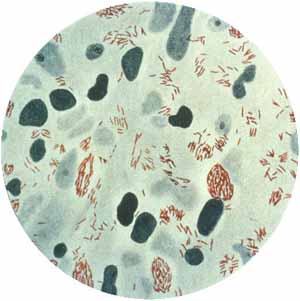

Leprosy is a disease caused by a bacterial pathogen, Mycobacterium leprae. M. leprae is well known in the lab scene for being a pain in the labcoat to work with. It thrives at temperatures just under human body temperature, and has a doubling time of almost 2 weeks, where most other species double in a matter of hours.

The history of leprosy is really interesting. While art from 600 B.C. illustrate what appears to be the symptoms of leprosy, the actual bacterium itself wasn't isolated until 1873. Dr. Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (say that 3 times and beetlejuice will appear) decided to name the disease after himself (Hansen's Disease), because his name wasn't sexy enough. But really, Dr. G. H. A. Hansen proved that science is the answer, because he dispelled the beliefs that leprosy was a curse from the heavens.

In the 1960s, the primary animal model was identified, and was found to be the only other reservoir, other than humans, for leprosy. Usually, animal models are mice, monkeys, and pigs, depending on the symptoms and effected tissues targeted by the suspect disease, but leprosy took a different turn. The only other reservoir for leprosy is armadillos.

Oh, hey!

Naturally occuring infection has been seen in some primate species, such as chimpanzees, mangabeys and macaques, but it is relatively rare compared to armadillos. It's estimated that 5% of armadillos in Louisiana have clinical leprosy.

Let me just backtrack a moment with a little anecdote:

When I told one of my best friends that I was going to write this entry, he was curious. Not only does he not have a biology background (he's a physicist, and I enjoy lovingly reminding him that he's not a real scientist (obviously joking)), but you don't really hear about leprosy every day. He's one of my favorite people because he genuinely shows a fascinated interest in the biological topics I bring up.

So, we got to talking about leprosy, and I was talking about how ridiculous it is that this study is just now being released, since scientists have openly known about armadillos being directly associated with leprosy since the 1960s. Sure, it's not within a doctor's scope of practice to know the historical information for every disease they encounter, but epidemiologists should have been able to trace the studies back to armadillos more efficiently.

As we were discussing this, I was getting more and more riled up, as I do when I get excited about science (naturally). As I'm ranting about this, I pull up pictures of armadillos and suddenly announce:

"I mean, come on! How did they not know it was armadillos? The lepromatous leprosy lesions look just like the skin of an armadillo!"

...I'll admit, this was not my finest moment, nor my most scientific, as this statement is far from factual. But I was hyper, and I couldn't stop myself from ranting. He stopped me immediately after that statement and said "Now, Elysse, that was probably the least scientifically progressive statement I've ever heard from you. Are you feeling ok?"

Now you have proof that I can be silly sometimes too. This is why I never go on dates.

Anyway, back to real science. Leprosy is alive and well in the Southern United States.

While transmission is thought to be through contact with nasal secretions, these secretions must have a gateway into the body, whether through the nasal cavity or through an open wound. I'm sure you can imagine that it's pretty hard to get leprosy from an armadillo, unless you're rubbing it against your face, or it happens to sneeze while you're face-to-face with it, and you just so happen to be breathing in at that very moment for maximum transmission. Yet, this study that was just released is convinced that armadillos are the source, as a majority of the cases are in individuals who have never left the United States in their lifetime. My first thought would be direct transmission from infection armadillos in the "craft" industry. I'm sure you've all seen armadillo shows, wallets and handbags. But who knows, its just a guess.

Don't worry about getting too worked up just yet. There are multidrug treatments for leprosy, depending on the stage in which you're diagnosed. Obviously, the sooner the better. Symptoms usually start off with numbness and the ability to be physically unaware of drastic temperature change in your limbs. There are many different stages of legions that can occur, and sometimes, an individual can be infected for months or years without showing characteristic legions.

Extreme cases of leprosy, or if the disease is left untreated, can result in crippling lesions that usually result in amputation. This is why treatment is urged, if available, as soon as diagnosis is confirmed. Unfortunately, a majority of the cases of leprosy, today, are in developing countries that have limited access to multidrug treatments for leprosy, and related symptoms.

While all of this is scary, researchers estimate that leprosy is not highly contagious, and that 95% of exposures do not result in disease.

"I'm going to kill you...once I get out of this bucket."